Stem Cell Transplants Improve on Current MS Treatments

Stem Cell Transplants Improve on Current MS Treatments

Stem Cell Transplants Improve on Current MS Treatments

A one-time stem cell transplantation treatment for multiple sclerosis showed improvements over the current therapies, according to a preliminary trial published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).

The process, called hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), temporarily shuts down and reboots patients’ immune systems, allowing the body to rebuild damaged nerve cells. The success of this trial serves as a proof-of-concept for the treatment, according to Richard Burt, MD, chief of Immunotherapy and Autoimmune Diseases in the Department of Medicine and lead author of the study.

“This opens the door for this therapy,” Burt said. “Now we can work on improving it, refining it and making it safer.”

MS is an immune-mediated disorder of the central nervous system often arising in young adulthood. It damages the nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord, causing symptoms that range from fatigue to paralysis throughout life.

The current disease-modifying therapies are intense and personalized drug regimens that patients must take indefinitely, even as its effectiveness can eventually fade, according to Burt.

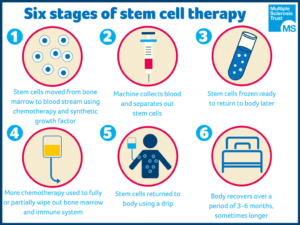

HSCT, however, relies on a different strategy: MS patients are given five days of immune-specific drugs to shut down their self-destructive immune system, then stem cells are transplanted into the patient’s blood. This produces new immune cells that several previous studies suggest may reset the immune system.

“When the immune system restarts in a non-inflammatory environment, it appears to default back to tolerance and stops the attack, allowing, depending on the stage of disease, for the body to repair itself to some extent,” Burt said.

Previously, HSCT found success in non-randomized patients in trials at Northwestern and elsewhere — including in Sweden and Canada, and at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and Duke University — but the current study is the first fully-randomized trial that tested relapse-remitting MS (RRMS) against the current treatment, Burt said.

In the trial, 110 patients were randomized to receive either HSCT or the traditional drug therapy. At last follow-up, disease progression occurred in 34 patients in the drug therapy group, but in just three patients in the HSCT group.

Patients in the drug therapy group had worsening scores on the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) — a method of quantifying disability in patients with MS — while patients in the HSCT group actually saw improvements in their scores.

In addition to being more a more efficacious treatment, HSCT has the potential to be more cost-effective than the current drug therapy, according to Burt.

“A full cost analysis needs to be performed, because the current drugs are very expensive,” Burt said. “I would anticipate, since this is just one treatment, that it may be a win-win: patients undergo a one-time treatment and get off of the drug regimen, while possibly saving money from a public health perspective.”

However, Burt cautions that further investigations are still needed to replicate these findings, and that the treatment needs to be used in the right type of RRMS.

Other Northwestern authors include Borko Jovanovic, PhD, associate professor of Preventive Medicine in the Division of Biostatistics; Roumen Balabanov, MD, associate professor in The Ken & Ruth Davee Department of Neurology, in the Division of Multiple Sclerosis & Neuroimmunology; Xiaoqiang Han, MD; Irene Helenowski, PhD; Amy Morgan; Kathleeen Quigley; Kim Yaung; Carri Alldredge; Allison Clendenan; Michelle Calvario and Jacquelyn Henry.